Layers: Weaving Narratives & Design to Construct Futures

A framework and tool designed by Ignacio Tovar, Noteh Krauss and Giuliana Mazzetta that uses objects as gateways to understand the complexity of the world we live in to reimagine our world for the better.

Introduction — Floating space junk & other objects

In the summer of 1977 NASA launched the Voyager 2 into space, a space probe that is now over 11 billion miles from earth, the farthest human-made object ever launched into space. What makes this object especially poetic are two disks placed on the probe. Constructed from gold, they are etched with a map back to earth and contain sounds and images capturing the diversity of life and culture on our planet. An object capturing the mystery of what it means to be human, an artefact of cold war space exploration, an engineering masterpiece — space junk floating out into the abyss.

While seemingly innocent, objects are gateways to complex realities and can serve as snapshots of the world we live in. They are constructed with layers. On one hand there is the materiality and the modes of production that bring them into being, often far removed from our immediate reality. And on the other end, they are made up of powerful, ubiquitous cultural narratives, narratives that we humans consume, narratives that inform and perpetuate our lived experience. Innocent objects or powerful tools, weapons and signifiers?

By revealing the complexity of an object, the fault lines of our current reality begin to become clear — fault lines marked by asymmetrical relationships between the have and have nots, producers and consumers, included and excluded and so on. Only by uncovering, flagging and understanding the roots of systemic challenges, can we begin to effectively reimagine and rebuild society for the better.

But who is responsible?

A call for designers

Designers are accountable. Designers are object makers. Whether physical or digital, designers devise and craft objects that are deployed onto reality — solutions that go on to live with real people and communities — who consume and produce them, who are directly and indirectly impacted by them.

In this regard, designers are accountable for what they bring into the world, and the resulting consequences. However, most designers are limited by design paradigms that view problems and scope of responsibility in vacuums.

As designers wield more impact — deploying tech-enabled solutions at a scale like never before — it is essential for them to proactively integrate accountability into their methods and ways of working, to harness tools that help them uncover and understand the complexity and consequences of what is being created head on.

Which brings us to the next question, how might we design responsibly and inclusively in such a complex world?

A new framework

Co-developed by Ignacio Tovar, Noteh Krauss and myself, Giuliana Mazzetta, Layers is a framework that dives into the relationship between the designer and the (designed) object, peeling into the constituent layers that reveal the evident and hidden narrative strands and structures that shape up our reality — and inclusivity. The tool encourages designers to take apart that which surrounds us, challenging the preconceived ideas hidden in the context through aesthetics and association. The framework aims to make a case for the future mindful, inclusive designer.

Bringing together methods

In order to achieve this, Layers brings together principles across of varying theories and methods. Specifically, inspired by:

- Interspecies design: Embracing the principle that humans and the natural world are interdependent, aiming to develop intersecting solutions that take human and nonhuman actors’ needs into account.

- Actor-network theory: Examining how everything is interrelated and how as we take more into account, complexity emerges.

- Design & society: Harnessing a contextual point of view to consider the dynamics of how design creates feedback loops of change — and how we can start hacking some of these feedback loops.

Layers Canvas

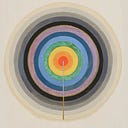

In order to untangle the object we devised this canvas that will guide you through the different layers. This canvas has many different ways of being used and read, but the main goal is to provide you with a framework that allows you to understand the designed thing at increased levels of abstraction and complexity.

Breaking it down

- At the centre of the canvas is the object. That is the innermost circle.

- Each of the lines that connects to the object at the center is a strand guide. Strand guides allow you to question specific aspects of the object. Here we are considering the following categories: Materiality, Production Process, Supply Chains, Institutions/Organizations, Markets, Trade, Consumers, Consumption, Communication, Semiotics and Meaning, Aesthetics and Use.

- One way of understanding the relationship of these strand guides is by reading them in a counterclockwise manner. In this way, they describe the process in which the object is made, supplied, traded, consumed and understood.

Frontend vs. backend

The framework can also be thought of in terms of its halves.

- If we divide it horizontally, we can describe two main ways of understanding the object. On the lower half we have the Front End of the object, which is linked to the Business Strategy and hence the viability of the object. Here, we are trying to understand the value creation process as the object exchanges hands and is consumed.

- In the upper half we have the Backend, or the process that happens behind the scenes; the way it is produced, understood and used. The way the design process captures needs and cultural values, and materializes them is the key to understanding this side.

Materiality vs. meaning

We can also divide the canvas vertically to show a different way of understanding the object.

- To the left, we have the Physical or Material aspects of the object. In this half we consider the way the raw materiality is transformed into an object and then is moved and shipped.

- On the right side we have the non-physical, the subjective qualities that are linked to the desirability of the object. When analyzing the strands related to this side, we are trying to dissect the way the object is perceived and consumed.

Strand guide

Additionally we can understand this canvas in terms of quadrants. The first and third quadrants are broken up into strands that describe the value creation of the object, while the second and fourth can tell us about the power structures that are held in place through the weaved thing.

When we map out each strand across layers, from the present direct relationship to indirect relationships and origins, we can begin to identify what are the power structures that are held by a combination of institutions, organizations, meaning, narratives and so on.

More specifically, we think that special attention could be placed in those strand guides that divide the quadrants.

- The first one is the Supply Chain strand guide, which make us understand the leap from manufactured object to commercialized product. What is the object made from? How is it manufactured? Who produces it?

- The second is the Trade strand guide, which describes the way the end user gets a hold of the object. Who owns and sells the object? What institutions enable or regulate it? How and where are supply chains set up? Which markets do they serve? Where and how are they sold?

- Then we have the Communication strand guide, describing the process in which the end users and general public come in contact in any way with the object. Who consumes it? Why do they consume it? How do they consume it?

- Finally is the Use strand guide, which comes to describe the way or ways in which the user interacts with the object. How does it make you feel? What does the object mean? What is the cultural significance? What do the aesthetics signal?

How to use it?

Placing an object at the centre of the canvas, we can start to dissect and uncover its complexity and network of implications. What strands sit directly around the object? What are the underlying origins behind these strands? Who does the object effect and how? How might my privilege as an individual inform and contribute to the existing context?

By mapping out the context, we can begin to understand the object more deeply as the invisible actors and systems that enable its existence and blind spots we might have previously overlooked emerge.

Already at this stage, the canvas presents itself as a useful tool for designers to gain an aerial view to consider interconnections and potential externalities of different actions. However, if you want to take it to the next level, participants can then enter into a more speculative space.

Once the context of an object has been mapped out, missed opportunities, problematic origins and omnipresent systems of power begin to make themself more clear. Flag them.

Focusing in on these flagged areas, participants can ideate and propose alternative solutions within the strands — designing for context. How might we reconsider the accountability for the objects deployment? Is there a way we can create deeper, positive impact? What does a more desirable and beneficial alternative look like?

For this section, we recommend solving from the perspective of diverse actors and stakeholders (ie. citizen, non-human beings, customer, business, community, ecosystem, etc.).

Once this phase of ideation is done, with new proposed solutions across the canvas, we then travel back inside, reconstructing the object at the centre in a way that negotiates and takes the intersecting solutions into account. As a result of the re-envisioned context, the object at the centre transforms completely.

Conclusion

Objects are the surface layer for complex realities — tying up and integrating diverse materials, activities and beliefs into unified wholes. By peeling the layers back from them, we are able to see interconnections and uncloak the invisible actors, forces and structures of power that enable their very existence.

Bringing it all together, how might we design responsible and inclusively in such a complex world? While we don’t have the perfect answer, we believe this framework and tool helps us to identify some key principles.

- Context — Exploring & understanding the role of context in shaping the products and services we design — thus expands our scope of responsibility as designers.

- Relationships — Through deconstruction of object, we can uncloak the complex relationships we engage with as designers.

- Blindspots — Through self-reflection and empathy we further uncover blindspots we wouldn’t perceive on our own at first glance.

- Intersections —Through reconstruction we take intersecting needs into account, reminding us we can’t design in vacuums for the needs of one human or customer segment.

With this tool, we hope that the creator can understand in a much richer way the full responsibility and accountability of that which is created, and as a result feel empowered to open up the conversation and playing field of where, how and what designers can and should be taking into account.